Now that our field school students have gained a good understanding of how early stone tools are made, it is time to find some stone tools in the field! And that is what the students have been waiting for! The Origins Field School has a tradition of visiting one of the most well-known hominin sites on the west side of Lake Turkana: Nariokotome. This is the place where the most complete skeleton of African Homo erectus, known as the Nariokotome boy, was found. The Nariokotome river has well shaded river banks, which make wonderful camping sites. What is more convenient is that from this centralized area, we can have easy access to a number of archaeological sites on the west side of Lake Turkana. And that is exactly what we did, a three-day camping trip to Nariokotome and sites along the way!

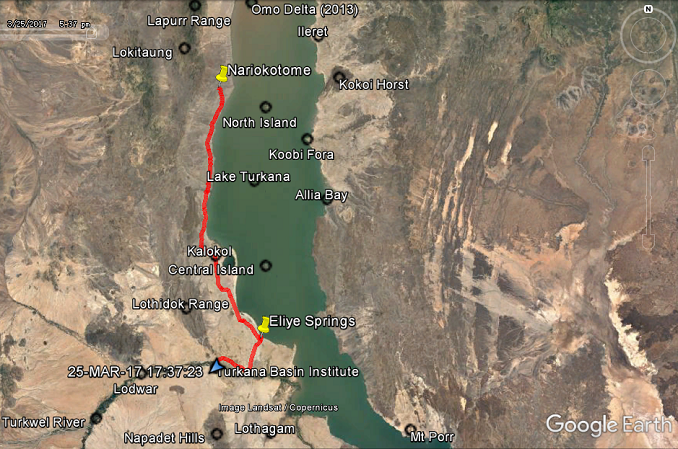

The route of our drive to Nariokotome

As mentioned in previous blogs, the Turkana Basin is a natural trap that has accumulated layers of sediments over millions of years. The sediments on the West side of Lake Turkana were laid down by the same processes that the students have learned in previous modules. However, there is one very convenient feature that makes them relatively easy to study chronologically: the sites are located in the south are in general older than the sites that are in the north. So as we drove up to Nariokotome from Turkwel, we were essentially driving through time: from older sections to younger ones!

Field School students and staff members are ready for the drive north

On our way up, we made a quick stop at a stone pillar site near Kalokol. Among the local Turkanas, it is known as “Namoratu’nga”, which means people that have been turned into stones! Of course, there is no such mythical being as medusas in the Turkana folk tales but where exactly did the stone pillars come from? Professor Hildebrand from Stony Brook University is an expert in the stone pillar sites on the west side of Turkana and she told us a fascinating story about the origins of the pillars. Archaeological evidence shows that the stone pillars were constructed several thousand years ago when the lake level was much higher. They have been associated with early pastoralists in the Lake Turkana region that are different from the Turkana people we know today. So by the time the Turkanas arrived in the area, the stone pillars were already there, hence the myth that is associated with the sites.

Professor Hildebrand introducing the Kalokol pillar site

Students observe the stone pillars

The stone pillars are made from naturally formed columns of basalt

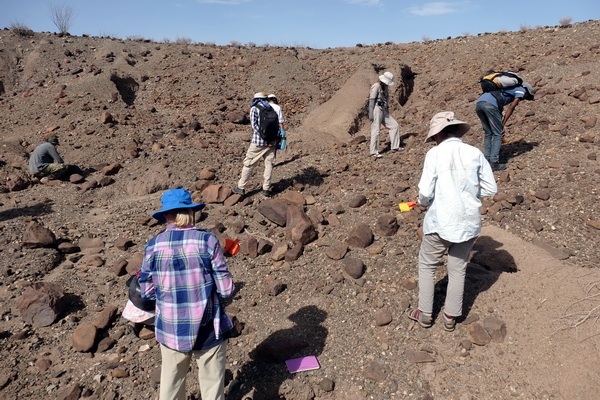

On the second day of our camping trip, we visited a site known as the Kokiselei site complex, where multiple sites of similar ages are located within a mile away from each other. The ages of these sites might be very close but the stone tool manufacturing technologies that are associated with the sites are quite different. Field school residential director Hilary Duke is an expert in the study of early stone tool technology and took us around the Kokiselei sites that she studies. At the sites, students appreciated the technological transition from typical flaking to shaping, and what it indicates for the hominin’s cognitive capacity. Although we don’t know who the tool makers are, we are sure that later stone tool production methods such as shaping, involve much more planning and abstractive thinking. Students also enjoyed a detailed survey and discussion about stone tools in the field. And of course, nothing is more exciting than picking up a stone tool that was made by a hominin some 2 million years ago!

Heading to Kokiselei!

Students appreciate one of the excavation sites in Kokiselei

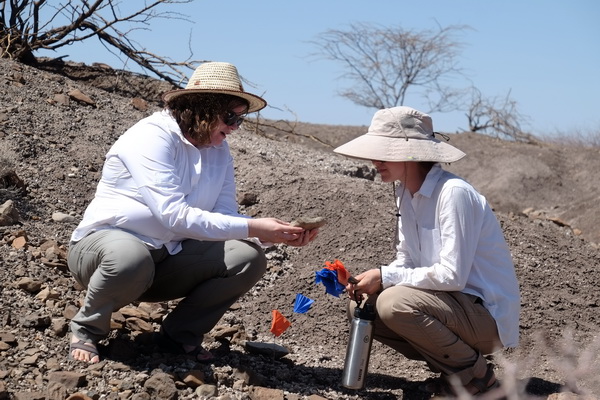

Field school residential director Hilary Duke explains features on a stone tool

Another excavation site within the Kokiselei site complex

On the search of ancient stone tools!

Esther and Goitom discuss what they find

Professor Hildebrand shares her insights with students

Felix carefully examining a stone core

Hilary shows Nicole how the stone tool was made

Students discuss what stone tools they see from the survey

On our way back to Nariokotome, we visited the Nariokotome boy monument, built on top of the hills where the skeleton was recovered. The fossil was initially found as a fragment of the forehead, by Kamoya Kimeu, one of the most experienced Kenyan fossil hunter at the time. Francis Ekai, TBI’s senior field assistant and fossil hunter, was just a 12-year-old boy and witnessed part of the excavation. He shared his story about how he was inspired by the discovery and later started working with hominin fossils and stone tools himself. Now the Nariokotome monument consists of an obelisk, a brass replicate of the skeleton and a marble slab engraved with the description of the site in three languages: English, Turkana, and Swahili.

Students standing next to the excavation pit where bones of the Nariokotome boy was recovered

A group photo with the Nariokotome boy Monument, and some locals

As the two-night camping trip comes to an end, it is time to say goodbye to Nariokotome. After a long drive, we stopped by the Eliye Springs Resort which is known for its beautiful beach view of Lake Turkana. What is better than taking a bath in the lake and enjoying a cold drink? It was truly a nice break from all the dust and weariness by sitting under palm trees and listening to the waves.

One corner of the Eliye Springs resort, with Francis Ekai (far right)

The beach view of Lake Turkana from Eliye Springs

The waves and the palm trees!

The Nariokotome camping trip was an incredible opportunity for our students to see some of the earliest stone tools produced by our direct ancestors. We hope that this trip can be the inspiration for our field students to come back to Lake Turkana in the future! Stay tuned for some new challenges in remaining of the Archaeology module!

A starry night at the Nariokotome camp