So far in the TBI field school, the students learned about the Ecology of the Turkana Basin, understanding how wildlife has greatly impacted the landscape, how vectors can spread disease, and how different animals interact. They saw zebra, giraffe, gazelle, elephants, baboons, cheetahs and they even got to pet a rhino! They then transitioned to a geological way of thinking, learning about the Sedimentary Geology and Geochronology of the Turkana Basin, becoming experts in identifying different geological formations, analyzing sedimentological properties, mapping entire regions, and most importantly interpreting past environments and what modern processes can tell us about them. Now as we enter the fifth week of the Fall 2016 Origins Field School, it is time to put together everything we have learned thus far and become master paleontologists!

This marks the start of the third module, Vertebrate Paleontology, taught by Dr. Ellen Miller from Wake Forest University. Dr. Miller is a biological anthropologist specializing in paleoanthropology, who has been working in the Turkana Basin for more than a decade! She and her co-PI, Isaiah Nengo, are currently directing field excavations at the Turkana Basin’s early Miocene site of Buluk. With her expertise in primate evolution, fossil mammals and skeletal biology, and from all of her field work experience, Dr. Miller is the perfect instructor to teach the students about the evolutionary past, and what working as a true paleontologist is all about.

Dr. Miller introducing the students to gene drift and gene flow

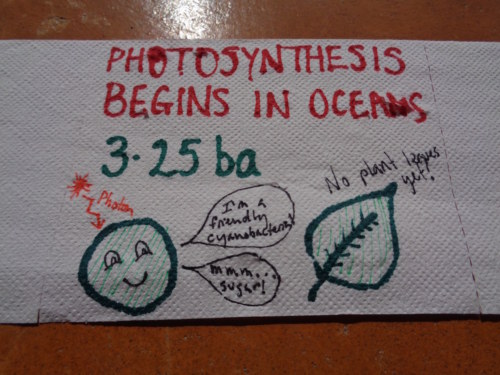

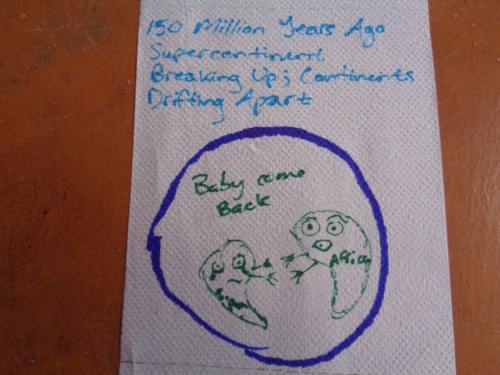

To kick off the paleontology module, Dr. Miller introduced the students to evolutionary theory before Darwin, Darwin and natural selection, and the Modern Synthesis. In order to value the true meaning of deep time, Dr. Miller had the students participate in a fun but educational exercise called the “Toilet paper timeline”! Here’s how it was done: The students had a roll of toilet paper that they had to unroll, divide and mark significant events throughout earth’s history at the appropriate periods. Since the earth is about 5 billion years old, each toilet paper square is equivalent to 12.5 million years and 80 squares is equivalent to one billion years of earth’s history. That means that one year is represented by 0.00000088 cm, a width that the naked eye cannot see! By marking from when earth was formed all the way to recorded human history, the students were able to see how much time truly exists in earth’s history! Also, they quickly learned how much toilet paper there really is in one roll…

Earth is formed…the rest is history

Toby and Danielle begin to unroll their toilet paper timeline

Morgan sketches when first life appears in the oceans

TA Jayde discusses with students how to organize their timelines

Natalie notes when cyanobacteria felt loved before the rest of Earth’s children arrived.

The students show Dr. Miller their timeline!

Millie, Yvette, Jon, and Natalie’s timeline seems to have taken an unexpected turn.

The students began to get clever with their pictures

Danielle and Carla work together to complete their timeline

Esther and Kathryn trying to hold down their timelines against the wind…funny how fast time flies…

Max’s timeline of Earth appears to have gone through some rough times.

Yvette makes some finishing touches

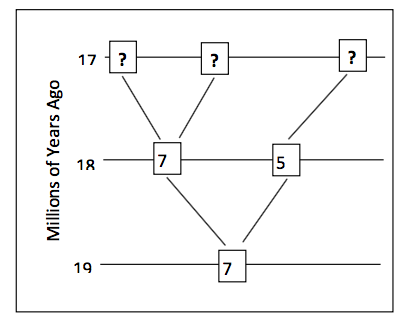

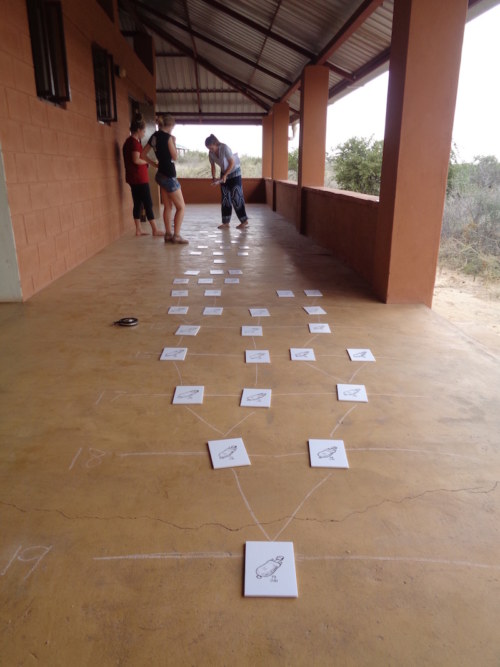

After a great introduction to evolutionary theory and the geological timescale, the students also learned about species concepts and systematics. Species concepts allow us to determine if two groups of similar animals are the same or different species, while systematics consists of sorting out who is related to who, once a species is defined. These are important concepts to understand in paleontology, and there was a lot of debate among the students about the best way to classify different species, with people on all sides trying to convince each other why one classification system triumphed the other. To further emphasize the true difficulty in species systematics, the afternoon lab involved students constructing their own phylogenic tree for, what Dr. Miller likes to call, “critters”. The students were given printed out pictures of about 80 of these assorted critters, chalk, and measuring tape, and they headed out to the mess hall where, after moving the tables and chairs, they would have plenty of room to construct their phylogenetic trees!

Example of a phylogenetic tree that the students had to make…but theirs was going to be much larger

TA Mattia and Dr. Miller help Danielle, Toby, and Carla determine how to start their phylogenetic tree

Kathryn, Emily and Millie lay out all of their critters based on how old they are

Jon, Yvette, and Natalie decide to group their critters based off of similarities before making their tree.

Esther, Morgan and Max debate on whether or not they correctly arranged their critters

As one can see, the students were not only challenged but they thoroughly enjoyed trying to figure out how each of these critters were related to each other. It was not only informative but a lot of fun to see how everyone’s phylogenetic trees turned out! This activity not only stressed the true difficulties systematists face, but it allowed the students to get their first dose of how a paleontologist should be thinking!

Next, the students will be learning about osteology and basic mammalian anatomy. Check in later to watch the students as they transform into paleontologists!