African mammals started out weird. When the dinosaurs bowed out sixty-five million years ago after a rough season with a few Indian volcanoes and a rough weekend with an asteroid near Cancun, Africa was already a continent adrift. Much like the modern island continent of Australia, home to unique mammalian lineages like kangaroos, Tasmanian devils, and platypuses, Africa would have been a very strange place to visit in its early mammalian days.

The Field School rolls into ancient East Africa. Left to right: Bailie, Cory, John, Leanna, Maegan, Francis, Natalie, Ingrid, and Marcel

Elephants wallowed in the mud like hippos while hyraxes – squat rabbit-like animals today – wandered the forests and plains as deer-like and rhino-like herbivores. Mixed into the herbivorous fauna was the elephantine Arsinotherium the earliest relatives of monkeys and apes, and the all-important extinct carnivorous mammals, the creodonts. But the exclusive African club couldn’t last forever. When Africa docked with Asia, the floodgates were opened and pulses of immigrants from the northern continents made their way into the bizarre world of giant hyraxes and buck-toothed elephants. For the next twenty million years, the mammals of Africa became more modern with the giant-headed creodonts fading out as dogs, cats, and hyaenas moved in and the hyraxes disappearing while giraffes, cows, and antelope found the continent a perfect place to set up shop. This was the Lion King-ification of the African ecosystem.

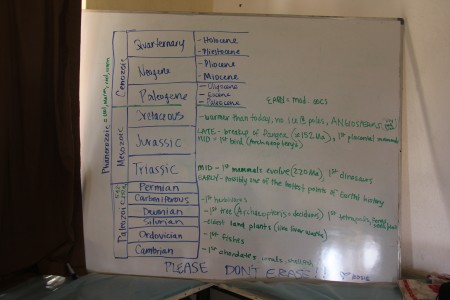

Rosie's geological timescale. The Miocene is near the top in the beginning of the Neogene. It runs from 23 million to 5 million years ago and was a time of major ecological transition across the planet, but was especially dramatic in Africa. The changes laid the groundwork for the evolution of a bipedal ape or two, but more on that next week...

The transition from the ancient to the modern in Africa is a Miocene story, a time period Dr. Mikael Fortelius and Dr. Meave Leakey have spent decades exploring. Our first field excursion for paleontology was to a newly discovered site near the Napudet Hills that may reveal these faunas in flux. The excursion was actually Dr. Leakey’s first visit to the locality since a lot of new material was discovered. Her field crew had carefully marked and documented several fossils, but despite years of work in the Turkana Basin, some fossils seemed unfamiliar, evidence that the site may be older than any other rock explored by the crew accustomed to the Plio-Pleistocene.

Meave Leakey and the excavation team. This crew is responsible for most of the spectacular discoveries in the Turkana Basin. Each crew member has a highly trained fossil search image and were very willing to help the students hone their fossil hunting abilities.

We piled off the truck and set out over the basalt cobbles that litter the place, evidence of the recent eruptions that built the nearby hills. Rob pointed out the artifacts that dotted the outcrop, though below the stone tools were much more ancient remains. Our first stop was to a large anthracothere tooth, an extinct relative of pigs and hippos that has been implicated in the origins of whales. Anthracotheres were part of the ancient African fauna, and were extinct by the end of the Miocene when hippos really got rolling.

Acacia, Rob, John, Holly, and Rosie comb the basalts, finding stone tools that have been deposited on the fossil teeth and bones in the recent past.

Dr. Fortelius explained how to recognize this ancient beast and we began a survey of the dried creek bed around the tooth. Everything was blanketed in basalt and the field crew’s honed fossil hunting skills were on full exhibition. Those of us less familiar with the conditions managed to find only a few scraps let alone the tiny cusp of a buried tooth.

They may be hard to see, but the flags mark the dozens of fossil bone fragments. Here an entire elephant seems to be buried, waiting for a patient excavator and preparator.

Our next stop was along a low slope where the teeth of a gomphothere, a relative of the mastodon and distant relative of modern elephants, had exploded from the outcrop. Spalls of teeth formed a thin crust around postcranial bones such as the ankle bone and long bones of the strange elephant. Immediately flags were distributed and the students began flagging all fossil material in the vicinity. By the time the hunt was over, more of the gomphothere had been discovered on the surface, including the other ankle bone. The entire squat elephant was hunkered into the hill along with the remains of a few giant hyraxes and some of the immigrant bovids that had begun their incursion into East Africa.

Can you find the early elephant tooth tucked into the rock? The Field School students can look at a cluster of rock and bone and know what they're looking at. This is a key life skill.

As we hiked back, Dr. Leakey and Dr. Fortelius kept an eye out for layers of ash that could be used to get a date for the site. A possible candidate was found with an ancient termite mound rising from the tuff.

Short pit stop. The soft sand and sticky clay was bound to slow us down eventually. (Photo taken by Dr. Fortelius)

You may remember Lothagam as a geological mecca we visited during the geology module with Dr. Craig Feibel. Then we were primarily interested in learning about the uplift of the ancient outcrop and the evidence of flowing water and changing climates preserved in the rock. This time we would be spending more time with the myriad fossils that carpet Lothagam that record the slow demise of ancient Africa and set the ecological stage for the diversification of our own bipedal lineage.

Rob is back in the zone and thinking about the ancient African fauna (or so he tells me) as we approach Lothagam.

The fossiliferous (fossil bearing) section at Lothagam begins with the animals that lived and died in the area 7.4 million years ago. Today, Lothagam is capped by the monolithic horst overlooking the intense oranges and reds of the Lothagam badlands. 7.4 million years ago, the badlands were a meandering river system. As we spread out from the lorry, the ancient denizens of the river system made themselves known: crocodiles of all shapes and sizes were mushed in with the abundant hippopotamus material. In a site so rich, it’s easy for a fossil hunter to only see the large bone fragments and miss the small teeth of primates and carnivores that may not be as obvious as an elephant femur.

A hippo's tibial plateau with a Lothagam plateau. The unfused growth plate on the top of this bone indicates this animal hadn't fully matured before it entered the fossil record. This photo is dedicated to my dad whose knees are slowly recovering from surgery and feel roughly the size of hippo's knee at the moment.

In order to more fully sample the site, Meave and Mikael introduced the field school to detailed transect techniques. The students spread out at arms length and tried to move in a straight line while collecting everything along the path. Easier said than done.

Sam searches for long bone bits. The modern bone in front of her is sitting very close to much more ancient elephant limb material.

Fossils were bleeding from the ground and it was easy to be distracted by all the bone and lose track of the line’s destination leading a few line wanderers to reset themselves every few minutes and a few discussions of where we were heading.. The blazing sun doesn’t make it any easier to keep on the straight and narrow either.

John with the finder's grin. He's gripping a beautiful hippo molar that he discovered during the survey.

Along the route, fragments of a hippo’s humerus came together along with the wrist bones and toes of an elephant who hadn’t fully reached adulthood (an observation made after an end cap, or epiphysis, was found near the animal’s toe bones).

Hippo humerus. Really, it's not all that funny. The head is to the right and the muscle attachment sites are to the left.

A second transect took place further up in the appropriately named Upper Nawata Member. At this point, East Africa had taken on a very modern character. If we could visit, there would still be a lot of unfamiliar animals, but the climate and the creatures – big cats, massive elephants, and large baboons – would have looked more familiar than they did in the lower section.

The second transect line. This time we were on a slope and our lines were even harder to hold. Despite bunching up, we still managed to recover plenty of material from the slope.

Back at camp we poured out the collection bags and everyone worked on identifying the finds. The elephant navicular was successfully identified by Sam and Aaron weighed in with some smaller carpels from the same animal. Ana found a long, thin toe bone of a terrestrial hippo. Yes, Lothagam had prancing hippos. Evolution is an amazing thing.

A seasonal riverbed that divides the badlands of Lothagam. A few weeks ago we walked through in search of cross-bedding and paleosols with Craig Feibel.

Once everyone had emptied their bags and identified the fragments that could be given names, we sat down to review the data. Our single day of sampling turned in an impressive collection of material that was carefully accessioned for further research in the dynamic world of the Miocene.