The Life & Times of

TURKANA BOY

The Life & Times of

TURKANA BOY

About Turkana Boy

Age, life, and death of the Nariokotome Homo erectus (KNM WT-15000)

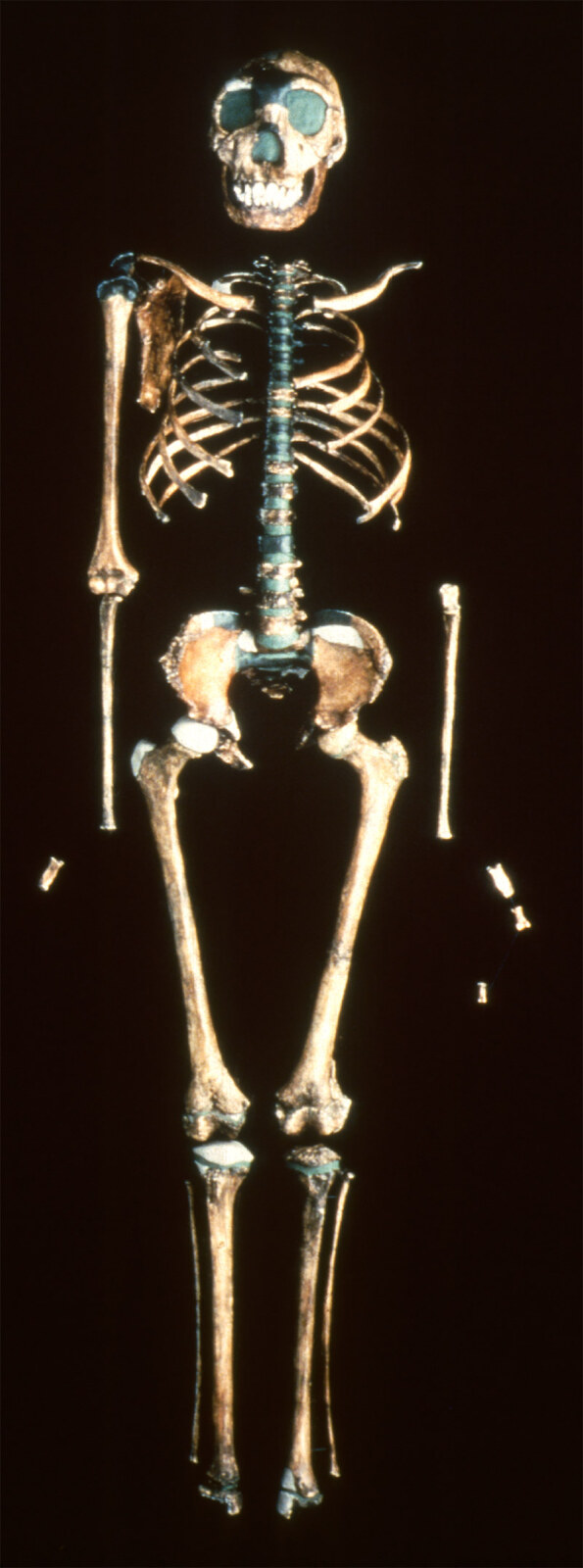

In 1984, Kamoya Kimeu, legendary fossil finder working for paleontologists Mary and then Richard Leakey in Kenya’s Lake Turkana Basin, spotted a section of skull on the shore of a dried-up riverbed, the Nariokotome. Patient and careful excavation revealed all but the feet of a 1.5 million year old skeleton. The boy the skeleton belonged to had shoulders, arms and legs that more closely resembled those of a modern human, so the skeleton was named “Turkana Boy”. His age, at the time of his death, was hard to pin down. Certainly, the lower jaw had incisors, canines and first and second premolars partially erupted, with third molars absent. The upper jaw still had milk teeth canines, with most of the permanent teeth partially formed. The features matched the tooth development of an 11-year-old boy.

His bones were still forming; the centers of formation on either side (epiphysis) had not fused in the middle of his long bones: his arms, legs and hips. This was further evidence that the boy was about 11. From the length of his thigh bone, we could tell he was about 5’3”. From the breadth of his bones, he must have weighed around 103 pounds. Modern human growth curves don’t really apply. Turkana Boy’s projected growth was recently recalculated using growth curves between human and ape norms. We now think he was around 9, beginning to experience a short adolescent growth spurt relative to ours that would have seen him grown (5’4” tall) by age 12.

How did he die? Two root fragments from a broken milk tooth, his second molar, caused an infection under pressure from his erupting premolar, and septicemia, blood poisoning, leading to an early demise. His body, sandwiched between two layers of volcanic ash half a million years apart, became exposed, with erosion, 1.5 million years later.

A boy with a head of hair, rather than fur-covered, whose proportions—arms, shoulders, chest and legs, resembled those of modern humans. He was named “Turkana Boy”. Overlapping with the australopithecines and an intermediate hominid form Homo habilis, Turkana Boy was exciting for multiple reasons.

To understand the significance of Turkana Boy, consider the most famous discovery at the time, from Hadar in Ethiopia, made by Paleoanthropologist Don Johanson’s team, an assembly of bones of a female australopithecine that was named “Lucy.” Lucy lived 3.2 million years ago. Her arms were long, and massive, her chest, funnel-shaped, like a chimpanzee’s; her fingers curved, like those of all tree-climbing primates. She spent at least a third of the time climbing trees, using enormous upper body strength. On the other hand, her feet, knees and hips, even the position of her head on her neck, were clearly adapted for a very rare trait in mammals, walking on two legs. Wide hips and lower rib cage framed a big belly that held a large gut, adapted to produce fat by fermenting a fibrous diet. Her gut, and the energy consumed to process the rough diet, made for a slowed gate. Her brain was one-third the size of the modern human brain, roughly on par with a chimpanzee’s.

The discovery of Turkana Boy tells us that a later protohuman form existed, barrel chested, rather than funnel-chested like Lucy, with a tucked-in pelvis, six vertebrae in the lower back (96% of humans now have 5) clearly evolved for walking, Homo erectus. His hands were free, as he walked, which suggests that he may have been able to carry a spear. This would have been useful. The landscape around Turkana Boy was shifting, forest cover giving way more often to open savannah, where, visible to predators, he would need to defend himself and compete for meat, fighting over scraps left by lions, ambushing animals, eventually actively hunting. A drop in the number of carnivore fossils around the same time suggests that his kind were successful competitors. The discovery of a group of male footprints suggests the formation of male social groups hunting among males targeting high-risk prey. Smaller teeth and jaws, smaller chewing capacity overall suggest Homo erectus ate meat balanced with a high-quality plant diet of berries, seeds, nuts, insects and grubs, tubers, bulbs and honey. Male hunters and female gatherers may have paired up. On the open savanna, encounters with natural fires would be frequent, and there is evidence that Homo erectus controlled fire and cooked, releasing more nutrients from food and making meat more digestible. A high quality diet of 50% meat meant that energy produced, particularly in the consumption of animal fat, could be diverted to brain growth over time.

His smaller vertebrae would have wrapped around a narrower spinal cord, which could not have handled control of his lung capacity to his mouth to form speech. The inside of his skull (endocast) shows traces of what would become our speech center, an asymmetry in extra space of the left brain that is longer than the right. One theory suggests this extra space was dedicated to motor movement programs that later provided the underlying structure for language, motor programming associated with the human preference for right handedness (75-90% of modern humans anywhere are right handed). Turkana Boy’s brain, larger than any before him, was about two-thirds the weight of our modern brain, so his behavior was probably very different from ours (in comparison, a two-year-old has 80% of the brain size of an adult). He could have been an accomplished tool user, and maybe a hunter, whose people made large and small stone tools, particularly, hand-axes for scraping meat off the bones of dead animals in a climate as hot as it is today in the Turkana Basin (average temperature).

Artist’s reconstruction of Turkana Boy.

Lab image of the reconstructed Turkana Boy skeleton.

East Africa during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene epoch was a transformative time in East Africa

2.6 million years ago to 11,000 years ago, in the Pleistocene era, weather began to oscillate for long intervals, cycling from warm/wet to cold/dry, while the earth’s elliptical orbit around the sun changed. The cycles lasted about 40,00 years lengthening to 100,00 years starting about 1.25 mya. In periods of global cooling, more water turned to ice and the sea level sank further, exposing channels that linked land masses. Islands were connected to mainland continents (Java, Sumatra and Borneo, for example, were connected to Asia). Grasslands took over, expanding and contracting over these cycles. Animal populations shifted, and more grazing animal species (antelope types) emerged. These migrated in pursuit of greener grass to graze on.

While the Sahara and the mountains of north Africa are barriers today, in the early Pleistocene, antelope, but also baboons, hippos and buffalo migrated through these all over and out of Africa and into the Middle East.

Extinct elephant from the Pleistocene. Illustration credit: Mauricio Anton.

Migration patterns of Homo erectus

Our direct ancestor ranged far and wide

Today our species Homo sapiens is the only member of the genus Homo inhabiting the planet earth. In the past the coexistence of multiple species in the same place at the same time is a general pattern that characterized the evolution of the human lineage. We now know that Homo erectus overlapped in time and space in East Africa with the species Homo habilis based on fossil discoveries of the two species from Kenya. Already with Homo habilis we see the slower, longer armed and shorter legged form that ate animal protein. Relying on scavenging, habilis was likely the last to get access to carcasses, surviving on what other animals couldn’t reach, smashing bone with rock to get at marrow. In Homo erectus, the walking and running form, the smaller teeth, jaws and incisors of a true omnivore formed.

Classifying finds as Homo erectus can be controversial since variability in traits definitely exists between populations from different geographic regions. Java Man, for example, the Homo erectus found all the way in Indonesia, had a huge projecting brow ridge. In Turkana Boy, the thinner and straighter skull bone behind the nose made it appear flatter and his lower jaw, slanted back from the straighter upper jaw gave him a ‘fallen’ chin. Most scientists agree that a cluster of shared features distinguish Homo erectus from all other humans. The first successful dispersal of hominins out of Africa was that of humans displaying the Homo erectus cluster of features. They were certainly hunter-gatherers, a remarkably versatile way of making a living, originating with Homo erectus in Africa close to 2 million years ago, and persisted until the present. Based on geological age and location of their specimens in the fossil record specimens, it is probable that bands of Homo erectus dispersed out of their Africa center of origin and rapidly expanded first into the Middle East, and then pushed north into Central Europe and east to China and Indonesia.

The distribution pattern of Oldowan/Achuelian stone tools made by Homo erectus broadly mirrors that of the fossil evidence. The oldest sites are in Africa at around 1.6 million years ago and the most recent approach the last 100,000 years. The geographical extent is also enormous, ranging across Africa, the Middle East, most of Europe and large parts of Asia. Is it however a real tradition across such a huge range? The Acheulean is an essential feature associated with the bio-cultural revolution. Components required for evolution to occur are still in play, particularly, environmental change and migration, geographic isolation (niches) and adaptation/natural selection lead to variation. However, the finds have caught up with the various arguments coming from those predisposed to favor the idea of multiple origins. Acheulian tool making reached Europe by at least 500,000 years ago and possibly as early as 900,000 years ago. Recently, 24 sites in southern China have now been found to contain Acheulian tools dating back about 800,000 years. 1.6 million years ago, the tradition originated in east Africa.

Homo erectus on the move.

Location of the discovery

Nariokotome, site of the Turkana Boy discovery

Lake Turkana, famously known as the Jade Lake from the turquoise color of its water, sits in a broad shallow basin situated between the Ethiopian highlands to the North and Kenyan highlands. Lake Turkana is also one of the northernmost of a series of lakes that lie in the great rift valley, the giant continental trench that runs south from Tanzania and into the Red Sea in the north. The two major rivers the Omo from the Ethipian highlands and the Turkwel from the Kenya highlands feed the lake. Today the weather is quite hot and dry because the two highlands block moisture creating a rain shadow and restricting the flow of air currents. Seasonal rivers running across the land cut breathtaking arrays of valleys exposing ancient rock layers preserving fossils from present, all the way back to the time when the dinosaurs roamed the continent. The current lake is less than 10,000 years old. The landscape during the time of the Turkan Boy would have been much the same, except the area was much wetter. A large ancient paleolake occupied the approximate location of the current lake at the time the Turkana Boy lived in the area now known as Nariokotome. The landscape was covered by a thicker cover of grasslands dotted with scattered trees.

Plaque located at the Turkana Boy monument at Nariokotome.

Technology of Homo erectus

Text to come

Stone tools are the oldest recorded example of a man-made object the fossil record has to date. This could have been the first foray into the making of man-made things. The way it develops over time gives us an idea of how, in the past, we began to think like humans. So far, the earliest stone tools discovered come from Turkana, Kenya, (Lomekwi 3 site in West Turkana, Kenya, S. Harmand et al, 2012, TBI and Stonybrook University) dated at 3.4 mya. In 2012, Sonia Harmand and her team from Turkana Basin Institute and Stonybrook University uncovered a core and flake pair in situ, dated 3.4 million years ago. The precision with which the flake was produced is obvious, it is a hefty, strong and sharp implement. What is also obvious is that the flake, rather than the core, was the desired finished product that would be used as a tool. The ‘flake’ in the clip linked below looks like it may have cut through thick skins and sliced pieces of meat. Evidence of use in this manner can be seen in cut marks that still are visible on bones scattered around it.

Among some paleontologists, the scientific term for Turkana boy is Homo ergaster, or the working man. He is an early example of a different kind of tool user. When Turkana Boy lived, the Acheulean uni and bi-faced handaxes were being made to serve a variety of functions in a variety of shapes and strengths. We infer this because of a group of handaxes found nearby, at a site called Kokiselei dated only 200,000 years earlier than Turkana Boy. Although only 50% of the surface of any of these shows working, the goal of symmetry is undeniable, which means the individuals who made these were able to reproduce an ideal pattern with repeated actions, in a variety of shapes for a variety of functions. A parallel skill might be the ability to read and follow maps. Once you learn how, the skill is available under any spatial condition anywhere. This is called allocentric perception and was thought to set us apart from all other primates (Wynn and Coolidge 2016, 205). Modern studies in primate cognition have thrown some doubt on this statement, where rewards motivate chimps to reenact an action pattern they have observed before.

Among the stone tools found with ergaster/erectus we find everything between core tools and finer flakes worked in a different way, with a focus on symmetry on two faces (sometimes these are called bifaces), and sharp edges on two sides of a specifically pear or tear-drop shaped tool. Acheulean hand axes were made by striking stones from boulders that varied in length (some flakes as long as 1 ft). Whether it had a tear-drop, triangular or oval shape, the ‘core’ fit comfortably in the hand, while the outlines were deliberately chipped to a sharp, narrow edge. At 1.6-1.4 million years ago, this technology spread throughout east Africa, and remained in use until 250,000 years ago, spreading throughout the world, from South Africa to Northern Europe, western Europe to India. In fact the name Acheulean comes from the French acheuléen after the type site of Saint-Acheul.

The hand-axes, while uniformly constructed with the same technique across the places they were found, were used to perform a variety of functions. The balanced symmetry of this technique is seen in smaller, discus-like versions that were hurled at prey; heftier versions were used to chop wood; sharper ones were used to butcher animals and clean the meat from the bone; some out-sized versions were, according to one theory, used for advertising the owner’s strength and status (flexing).

Acheulean technology developed much later, in the lower Paleolithic, into the Levallois technique, arguably a more efficient way to produce the tool. The material was chosen, the core shape was chosen, with attention to the material used, and the core having a flat platform surface which could be chipped along the edges to make a domed shape. Then an expert ‘knapper’ would deliver a mighty ‘strike’ to crack the ‘tortoise’ (because the multiple strikes created a tortoise-shell like pattern) off of the core. The result was a highly replicable ideal form that would later be adapted in production of spear and arrowheads.

Levallois flake obtained by the preferential Levallois method. Image credit: José-Manuel Benito Álvarez.

Acheulean hand axe. Image credit: West Turkana Archeological Project.