“It was the color, the texture, the shape that stood out in the landscape and when I examined it for a closer look someone in the distance started shouting: Hominid! Hominid!”

~ Anjali Biju, Graphic Design MFA student at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) and EcoDepot intern.

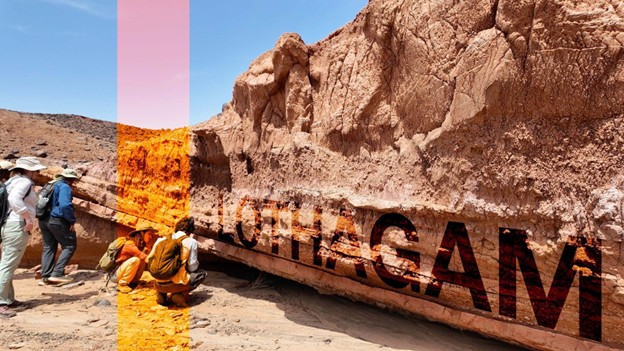

Those shouts, emanating from the skilled field team of local Kenyan TBI staff, were well-earned. What Anjali, a Master’s student in Graphic Design at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), had spotted during a dusty mapping exercise in northern Kenya turned out to be a hominin tooth more than a million years old. For someone trained in design rather than geology, the discovery was as unexpected as it was unforgettable. For the group, it was a vivid reminder that even a chance find can shape decades of research at TBI.

And yet, that was the point. The inaugural TBI/SBU Geology Field School was designed as an experiment: what happens when geology, marine biology, journalism, poli-sci, and design students spend three weeks together in the Turkana Basin? How might fresh eyes, trained in a diversity of disciplines, help interpret landscapes in new ways? Unlike most field schools throughout the US, students were tasked to look beyond the geology, equipped with the unique tools of transdisciplinarity to reframe the questions being asked and reshape the trajectory of their hypotheses.

Learning the Land

While the program started in metropolitan Nairobi, students flew to TBI’s remote campuses at Ileret and Turkwel in Cessna prop planes. They mapped sedimentary sequences, traced ancient lake beds, and tested their interpretations against the landscapes themselves. Each exercise pulled them further from the abstractions of classroom geology and deeper into the lived complexities of fieldwork: stratigraphic puzzles that refused to line up neatly, fossil evidence that raised new questions instead of supporting easy answers, and an endless amount of rock waiting to unsettle every certainty we carried into the field. Or, in the words of a student, it was less about finding answers than about unlearning assumptions.

Sketchbooks in hand, the students presented their maps to Dr. Bob Raynolds of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science – a rare chance to collaborate directly with the scientist whose decades of work helped articulate much of Turkana’s geology. Alongside Dr. Louise Leakey, they experienced first-hand the importance of field discovery protocols, using a simple Polaroid to extrapolate a transformed terrain and relocate sites excavated decades earlier by her father, Dr. Richard Leakey – sites that had yielded some of the most important fossils in human history. One of them, long thought lost, was identified when the group noticed a small cairn in the photograph that still stood in the landscape, obscured by erosion and vegetation. Here, the students were challenged to imagine the past landscapes and the conditions that allowed those fossils to be so precisely preserved. Back at the Ileret field station, they gathered around Dr. Raynolds to sift through the trove of paintings, created in close collaboration with an artist, that brought to life the ever-changing environment of their immediate surroundings throughout the last millions of years.

Design Research - Analysis 1 - Contextualizing the geologic narrative

Design Research in the Field

At its core, Design Research is about learning from people – their needs, their values, and their lived realities. Where Scientific Research evaluates existing evidence through systematic data collection, Design Research generates new possibilities through the cumulative gathering of human experiences, with empathy as its central tool. In this sense, Design Research doesn’t replace Scientific Research but reframes it, reminding students that knowledge is synthesized in dialogue with communities.

It is through this practice of social design that the Geology Field School was built as an opportunity for all participants to reimagine how scientific fieldwork is conducted, who it might engage, and how. Architects and educators Desmond DeLanty (EcoDepot) and Thomas Gardner (MICA) worked with the faculty to shape the program as a space to foster science and design synergies, elevating both bodies of work in the process.

Design Research - Analysis 2 - Community, creation, and color

The design group’s goals were clear: to cultivate careful observation, to train students in active listening, and to reinforce the principle that science can only contribute to contemporary challenges when it is informed by working with communities, not apart from them. To make this tangible, they documented the daily rhythms of geology fieldwork – students measuring stratigraphy, researchers debating geological context, Turkana and Daasanach community members moving through their own routines – all captured side by side. These films and sketches become tools for reflection, allowing a broader audience to examine how science unfolds in practice and how inseparable it is from the people and places where it happens.

On the students’ side, their final task was to interview members of the TBI staff and write essays about what they learned. The point was not only to gather stories but to practice careful observation and listening – the core of design research. Francis Ekai spoke of the challenges in communication between local knowledge and scientific research; James Ayube reflected on the daily work of sustaining life at a desert campus; Christine Atabo described the tenacity required as one of the few female scientists at TBI; and Tom Odeyo offered insights into the relationship of science to a contemporary Kenyan’s education journey and the challenge of retaining talented students and future scientists.

The result was a recognition that fieldwork is never just about data: it is equally about relationships, responsibilities, and the contexts that make discovery possible. In Turkana and through TBI, fossils emerge from the ground, but their meaning comes from the people whose work, resilience, and vision sustain the science.

A Fortuitous Discovery

Design Research - Analysis 3 - Discovery and stratigraphy

The tooth was not planned – no syllabus could script that moment. But its chance discovery drove home a lesson no lecture ever could: world-class science often begins with a sharp eye and a dose of luck. What mattered was not the thrill of the find, but the discipline that followed. Students learned why TBI’s protocols are clear: fossils must stay exactly where they are found until trained staff document and preserve them. Context – the geology, sediments, and associations – makes the science. That the tooth survived at all is remarkable, but the rapid burial in fine sediment and the unique chemistry of Turkana’s soils conspired to preserve this fragment of a life once lived.

In this case, context is everything: a single tooth could belong to any number of possible human ancestors – Homo erectus, perhaps, or one of the other hominin lineages that roamed the Turkana Basin more than a million years ago. Only meticulous laboratory analyses will be able to sort the possibilities apart – opportunities created for a multitude of students, local TBI field staff, collections, and preparators, as well as external specialists.

A tooth is, in many ways, a tiny time capsule. Its crystalline enamel can lock in isotopic signals that reveal the individual diet – whether they chewed mostly grasses, leaves, or meat – or can hint at the climate the individual experienced – wet or dry, stable or unpredictable. Unlike bone, enamel resists alteration after burial, making these signals unusually trustworthy. And increasingly, geneticists are coaxing fragments of ancient DNA from within teeth, opening new windows into population histories and evolutionary relationships.

Through this shared experience, Anjali and her peers saw firsthand how patience, precision, and respect turn such a discovery into meaningful research. More importantly, they realized that as students, they were not just learning about science – they were actively contributing to it.

POV - You’re a Graphic Design Grad Student, first time in the field, it's hot and your water bottle is a bit warm, but you just discovered a million+ year old hominin tooth in the desert.

* A note from Anjali Biju *

While working in the Turkana Basin, I never expected my skills as a visual designer to play a role beyond documenting the expedition through sketches, photography, and film. But one day out in the field, among the gravel and rocks on the ground, I noticed a small object that looked different from the rest. I picked it up and saw that it was a tooth. At first, I assumed it was from a monkey or an ape, since TBI’s field team had already come across a few earlier that morning.

It wasn’t until someone from the team shouted “Hominid!” that the magnitude of my discovery started to set in. I was stunned. From the beginning, the students and researchers had spoken about how rare hominid fossils were, so rare that even seasoned scientists working in the region for their whole careers seldom encountered them. It came down to a mix of luck and the ability to notice subtle details. And here I was holding one that is at least 1.4 million years old.

As my teammates gathered around, I felt a mixture of disbelief and humility. The find was extraordinary but I was also aware of the years of dedication, research, and patience others had invested in this landscape. In that moment, I realized my contribution extended beyond design. My way of seeing as a visual designer had led me to a hominin tooth, a discovery that will stay with me as one of the most unexpected and profound moments of my journey.

That moment also showed me the value of bringing an art and design perspective into a scientific landscape. The same habits of observing, seeing, and interpreting that guide my creative practice can open up new ways of synthesizing from and with the field, showing us that creativity and science are not separate pursuits but partners in discovery.

**

Science in Context

This field school illustrated that landscapes are not just archives of the past but central to life today. At Ileret High School, Kenyan students spoke with the group about the rising lake: how it is reshaping livelihoods and local economies, reducing long-standing conflicts over scarce grazing pastoral lands, and forcing communities to adapt together around a shared resource – a lake in the desert. At Turkwel, students met with Chief Sarah and embedded themselves in her community to learn about the traditional practices of building, weaving, and water management.

Through these exchanges, U.S. students came to see the lake not just as a feature on a geologic map but as the heartbeat of the desert, shaping both ecosystems and human relationships. Every systolic expansion of the lake into the desert’s veins, a beat per hundreds and thousands of years that superimposed a narrative stratigraphy of rocks and sediment to preserve stories of past landscapes. The communities of the Daasanatch and Turkana carry living knowledge of how the lake continues to shape the beat of life in the Basin. For the students, it was a reminder that understanding Turkana’s history and its future requires listening both to the geology beneath their feet and to the people who call this place home.

Carrying the Lessons Forward

For Stony Brook University and TBI, this field school was more than another summer study abroad program. It was a new model for how science can be taught – collaborative, cross-disciplinary, and deeply connected to the communities where it takes place.

Join us this October at the TBI@20 Conference, where you’ll have the chance to meet and hear directly from the first cohort of the Geology Field School as they share their discoveries and experiences.

Registration is now open for the 2026 TBI Geology Field School. For more information, and to stay up-to-date on our continued outreach, contact Dr. Marine Frouin (marine.frouin@stonybrook.edu). You can find the videos of the ongoing work here: www.ecodepot.supply/turkana-basin

This first field school was made possible through the generosity of anonymous donors, and we extend our deepest thanks. Their support created an experience that was transformative for everyone involved and rippled outward, strengthening research, education, and community relationships in Turkana.

All original artwork was created by EcoDepot and Anjali Biju in an ongoing effort to observe, reflect, and synthesize how the cultural and physical landscapes of the Turkana Basin might collaborate to create new opportunities for the community, scientists, and creative disciplines to thrive through TBI. Photo credits are attributed to EcoDepot. Written content by Dr. Marine Frouin, Desmond DeLanty, Thomas Gardner, and Anjali Biju.