Photo: Esther Kadaga

Our journey through the Archaeology module is coming to an end. We had a few site visits this week and one of the activities the students got to do was archaeological surveys. Archaeological surveys are useful in helping archaeologists to identify where best to excavate. The field team scans the area of interest for artefacts and use flags to mark the finds.

Lining up for the archaeological survey. Photo: Esther Kadaga

Students doing the survey. Photo: Esther Kadaga

Meaghan flagging an artefact. Photo: Esther Kadaga

Students busy at work looking for artefacts. Photo: Esther Kadaga

Photo: Esther Kadaga

The distribution of the artefacts in a target area would help to determine whether a particular spot would be particularly rich when the excavation is undertaken. However, one should not be quick to start an excavation where the artefacts are abundant. This is because factors like topography of the area may be playing a role in how the artefacts are distributed. Erosion by wind (deflation) or water (fluvial erosion) could be moving small particles of sediments a little further down a slope displacing the artefacts from their original context. The best bet would therefore be to set up an excavation where one would expect to find some of the artefacts still in situ, unaffected by erosion. For this, careful survey needs to be conducted.

Flags showing the artefacts the students identified. Regina examining an artefact. Photo: Esther Kadaga

Very few artefacts at the very bottom of the slope. Most were a bit further up and could be eroding from the top of the slope. Photo: Esther Kadaga

We visited Lothagam, which has important sites that record significant changes in cultures of inhabitants of the Turkana basin during the early and middle Holocene. The lake levels were fluctuating during these periods and could have led to the shift from a fisher-hunter-gatherer lifestyle to pastoralism. During the early Holocene (10000-7000 years ago), the lake was at a high stand up to about 80m above the current lake level. This corresponds with the African Humid Period when most parts of the continent, north of the equator, were wetter. Barbed-bone points (harpoons) have been found in the early-middle Holocene paleo-beach deposits at Lothagam. The fisher-hunter-gatherers could have used them for fishing. Pottery and stone tools are also present. Going into the middle Holocene, about 5000-4000 years ago, it got drier and the lake levels dropped by about 50m. New types of pottery emerge as well as the setting up of communal cemeteries. Bones of livestock like cattle, sheep and goats have been recovered from these middle Holocene deposits suggesting that the inhabitants had started herding. Pastoralism seems like a mode of coping mechanism to the drier conditions that characterize the basin even to the present day.

At Lothagam: Where the students are standing, during the early Holocene high lake stand, they would have been under water Photo: Esther Kadaga

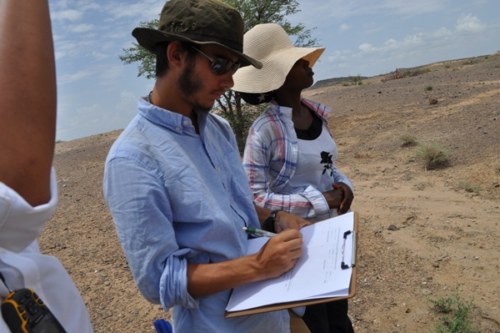

Prof. Hildebrand guiding the students on how to fill out an Archaeological survey form for the Lothagam site survey activity. Photo: Esther Kadaga

Students conducting an archaeological survey at the Lothagam harpoon site. Photo: Esther Kadaga.

Rohan, Matt, Ann and Gill working at their survey site. Photo: Esther Kadaga

Matt filling out a survey form. Photo: Esther Kadaga

Prof. Hildebrand assessing Kifle, Regina and Ulla’s survey form. Photo: Esther Kadaga

Perhaps a question that at one time some of us have come across is the relevance of Archaeology to contemporary issues. The students got to walk in an archaeologist’s shoes for a day when they visited the cultural heritage sites that Lodwar has to offer. One of the sites was the Kenyatta House, where the first president of Kenya, Jomo Kenyatta was imprisoned (1960-1961) by the British colonizers. Thereafter, the students had to draft proposals for what they thought would be needed to preserve and conserve the sites. They got to see the important role that archaeologists play in the preservation and conservation of cultural heritage sites. Cultural heritage sites are a valuable economic resource. They can also act as symbols that help foster national unity especially when they represent shared experiences like, struggle for independence from colonial rule.

In Lodwar. Photo: Esther Kadaga

Entrance to the Kenyatta House. Photo: Esther Kadaga

The Kenyatta House. Photo: Esther Kadaga

At the Tribal court house, in Lodwar. It was used in the colonial era as well as for some time during the postcolonial period. Photo: Esther Kadaga

Justus, a National Museums of Kenya official, explaining the history of the Tribal court house. Photo: Esther Kadaga

Photo: Esther Kadaga

As the field school comes to an end, the students are sad to leave the Turkana basin which has been their home for the past nine weeks. When they leave, they will take with them the fascinating insights that they have learned about the evolution of life forms on earth and the critical role that the Turkana Basin plays in the unfolding of this narrative!